- Home

- Nicole Burr

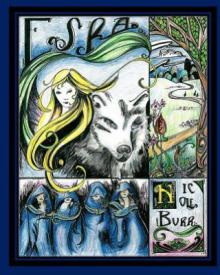

Esra Page 2

Esra Read online

Page 2

Pausing for a moment to let the memory wash over them, Esra could see the fiery little creature in her mind as if it were yesterday. Smiling, she slowly stretched and lifted Meshok’s head from her lap so she could stand. Steadying the bucket with her free hand, they began the slow walk back to the house. Esra always had to concentrate when she fetched Water, a seemingly simple task. Her lack of grace usually meant that at least a third of the Water would slosh over the rim of the bucket on her return, making it necessary for her to make two trips to the cool edge of the stream.

Her grandmother, who always seemed to sense when Esra was near the house, was standing with the thick wooden door propped behind her. “Looks like we’ll be gettin’ some rain. Better hope yer grandfather gets home in time to avoid the brunt of it.”

He had left an hour earlier to make a trip into town for some spices. They had spent the day yesterday drying and wrapping Herbs to trade at the general store. Esra looked outside the window at the clear blue skies and tried to understand how her grandmother could always make such unfounded yet accurate predictions. She had no doubt that there would be a storm and that her grandfather would be back before it started. Nothing, not even an act of nature, could catch her grandparents off guard.

After making the required second journey for more Water, she took her place at her grandmother’s side to help with the Vegetables.

“How go yer studies with Cane?”

“Oh, good,” Esra nodded. “We’re currently studying Elvish history, which I must admit is very interesting. But I daresay I shouldn’t get too involved, fer Cane never does like to stay on any one topic fer too long.”

Her grandmother nodded silently in agreement as she poured the second bucket deftly into the cooking pot on the Fire. Despite her small, frail frame, she still had the strength and endurance to continue her self-sufficient way of life. She was a woman of structure and habit, finding comfort in completing her daily tasks through repetitive, ritualized movements. Every morning she swept up her long white hair into a tight bun and washed her face with Lavender Water, patting it dry three times. She took the folded apron from the chair next to her bed and tied the familiar knot at the small of her back before sliding on her boots, left one first. The only hint of deviation from this order and tradition was when her face crinkled into joyous chaos when she smiled.

In spite of all this tenacity, Esra worried how much longer her grandmother’s strength would last and each season expected to see the decline begin. She looked at her grandmother, now stirring the pot in steady, circular motions and decided it was as good a time as any to bring up a delicate topic.

“Grandmother, I know that we have discussed this before, but I have been thinking more on the subject, and I wish to make a proposal.”

She gave Esra a tired smile, sensing what was coming. “Ye do, eh?”

“Yes,” Esra stated, gathering courage. “Ye and grandfather are getting older, and although I enjoy my studies with Cane, it pains me to think that I am not here more to help ye with the chores and the farming. Some of the work that grandfather does in the fields would be difficult fer one half his age and twice his size. However, I realize that my studies are important to the both of ye, although what future it would bring me, I don’t know. There is no need fer a teacher in the village and I have no intention of leaving here to pursue knowledge in a larger city. Nor do I have the urge to become assistant to a merchant or tutor fer the wealthy. So instead I will offer ye both a compromise. Why not let me cut my time with Cane in half? I could go there fer three afternoons a week instead of six. I will still be able to have my lessons but I can be here more to help.

“I am not in any way suggesting that ye are unable to do things fer yerself,“ she added quickly, “but I would like to be able to feel that I pull my weight in this family. And as wonderful as it is to be studying new things all the time, it seems fairly useless.”

Esra paused to gauge her grandmother’s reaction, who had continued to stir the soup pot in a slow, rhythmic motion.

“And how long have ye been preparing to say that?” Her grandmother chuckled.

“Aye, a few nights,” Esra flushed red. “I’ve been practicing my delivery to Meshok. She’s a fair audience but doesn’t give much in the way of advice.”

Meshok lifted her head from the rug where she was sleeping at the sound of her name and yawned largely to show her disinterest in Esra’s sarcasm.

“My dear child,” her grandmother said, leaning the spoon against the side of the pot and coming to place her hand on Esra’s shoulder. “Ye really needn’t worry so much. I am still very capable, as is yer grandfather. Yer studies are very important to us, and they will someday prove to be very useful, whether ye know it or not. Yer right about some of the field work being too hard, but it is also too much fer ye. We have already talked to Baelin, and he will be coming by now once or twice a week to handle some of the heavier work. We offered to pay him, but instead he asked that we allow him the use of our Fariel, since he has no Horse of his own. So yer worries are unnecessary and although I applaud yer sensitivity, we are managing just fine. Nothing would make yer grandfather and I more proud than if ye continue yer learning with Cane as planned.”

It was hard to argue with her grandmother, especially when she spoke so plainly. But Esra was not ready to concede defeat just yet.

“Then I must ask, at least, what is the purpose of my studies? I am not willing to leave Sorley. Ye and grandfather are all I know. And while my learning…” she tried to think of the best way to describe her feeling, “fulfills me, it is not, as I said, very useful here.”

“Well, I regret that ye feel that way,” her grandmother dissented with a frown. “But Esra, ye must understand that someday, maybe after we are gone, ye may want to leave this place. And even if ye do not, it is not fair to say that this knowledge is ‘useless’. Training of the mind is just as important as training of the body. They may not produce the same visible effect. Sow a crop in a field and ye will have a harvest to show fer it. But the results of wisdom are much harder to see, harder to measure. Ye must trust that yer grandfather and I are doing what’s best fer ye. We want ye to have this opportunity, and despite what ye think, ye were born fer such things.”

Her grandmother took her hand from Esra’s shoulder and returned to the soup pot, indicating that the conversation was officially over. Had Esra been more inclined towards stubbornness, she would have argued further. But she was generally open-minded and adaptable, perhaps recompense for a childhood without any parents or siblings, or due to her studies with Cane which forced one to see things from multiple perspectives. There were still many times she wished she could be more obstinate, especially in situations like this, but she had an appreciation for knowing when acceptance would serve her better.

She also recognized that what her grandmother had said was true, especially about her talent for learning. Aside from appearing like a wandering vagrant, Esra maintained a rare grace of mind. She was clever, insightful, and soaked up knowledge without abandon or prejudice. Even though Esra had few friends her own age, all the townsfolk respected her cleverness and foresight. She was especially regarded for her skill in preventing heated arguments between wives and their drunken husbands with a well-timed piece of wit.

But Esra also had a habit of daydreaming mercilessly, her head constantly full of imaginations from books and her own making. This greatly added to her distracted and accident prone state, and it was not unusual for her to be unable to identify a certain Tree she passed twice a day or the color of the general store she visited once a week. And the amount of times she had gotten lost on their own property was astounding.

Although she was entirely unobservant of her surroundings, it did not give her the air of being foolish. She simply preferred the unlimited imaginings of her own mind to the boring restrictions of reality. She liked to think that this gave her great creativity and tolerance to change, which had helped her adapt to a life in

Sorley without her parents.

Her grandparents had sent her to study with Cane as soon as she could walk. While the other children in town worked the fields beside their families, Esra was learning about mathematics and geography of the Old Kingdom. The townspeople, however, remained oblivious to the true purpose of her visits with Cane and believed, upon the adamant insistence of her grandparents, that she went there each day to cook and clean for the old man. When Esra was younger she questioned the motives behind such secrecy, but her Grandmother told her “to appear humble in this town, ye must ne’er force others to face intellectual ignorance by strutting about yer accomplishments”.

Although unsure of what this meant or why it was so important, she trusted her grandmother to understand the workings of the village where she had been all her long life. Most people had a notion that Esra being hired to cook anything, especially when that task involved Fire, was absurd for such a clumsy girl. But if they did entertain such thoughts, no one would dare say these things aloud. Her grandparents were well respected people, known for their generosity and kindness. They had managed to help many townsfolk while simultaneously earning the trust of those they helped by keeping such business between themselves.

And even though their household portrayed the epitome of order, they were also a very jovial bunch. There were nights when they would all sit around the Fire and in a special streak of silliness, her grandfather would stand before them and pretend to be a Bard. He would devise songs like “I’m richer when I’m drunk because everything seems to double”. Esra and her grandmother would be bent over in their chair in a fit of laughter as he tried to maintain a stance of mock seriousness, which eventually would twitch determinedly at the corners of his mouth until he joined them.

They were also some of the wealthiest villagers, but not so much that it separated them unduly from the rest of the town. Esra often wondered where they had gotten such money, and when she asked her grandmother, she spoke of names and places unheard of, and an inheritance that came from distant relatives. It allowed them to live in comfort, and keep a yard full of fat Animals, although they still preferred to grow many of their own Vegetables and Herbs.

When children asked their mothers why Esra, already a strange creature to be twenty and unwed, could do things such as wander about in the forest while they spent every waking moment bent over a plow, they were quickly hushed and told firmly that good people were entitled to the privacy of their own way.

There was a gentle knock at the door and Esra wiped her hands on her smock to let her grandfather in. His hands were teeming with baskets of heavily scented leaves and crisp, paper wrapped parcels. His sparse white hair was sticking up on its ends as it always did, giving him a look of playfulness and mischief that Esra treasured. He stood only as high as her nose and had grown plump with age, with cheeks that seemed to be permanently rosy.

“He is worse to send a’shoppin than a woman,” her grandmother chuckled.

Esra laughed under her breath as she helped unload the overflowing pile of goods in his arms. It was true that her grandfather never went into town without returning with something completely unnecessary for his two favorite women. For Esra it was usually a sweet treat to savor, and for his wife something more practical but relatively unneeded. This was the small thorn in their realm of predictableness; her grandfather’s ridiculous shopping habits. He handed his granddaughter a small wrapped package which she knew from the smoky rich smell contained sweetened Corra Nuts.

“And this is fer ye, my lady,” Esra’s grandfather bowed to his wife as he swept open his coat dramatically, pulling out a wooden contraption. It was short and fat with four protruding, rounded stumps. His eyes shone with pride as his wife took the item into her hands.

“Wonderful!” She exclaimed. There was a pause as she turned the item over. “What is it?”

Grandfather loved these moments for telling what the thing was probably more than the act of giving it. “Why, it’s a bread beater, of course!”

Her grandmother turned to Esra with wide eyes, who shrugged to show that she was also quite mystified.

“See,” he slid the wooden debacle out of her hands and waved it around in front of his chest. “Ye use it to knead bread!”

“Oh!” Grandmother clapped her hands cheerfully as she watched him flail about. It did not matter that she would probably never use the thing correctly, or if she did, would decide that her own hands were more efficient. He had never failed at being able to surprise them with a preposterous gift. The village was not a particularly large one, but Mr. Sturik, the owner of the general store, had learned to order these strange items for one particular customer alone. No one else seemed to have the desire, nor the extra coin, for such bric-a-brac.

The general store was located at the town center along with the five bedroom inn, alehouse, apothecary, grain mill, and other various small shops. The village of Sorley was shaped like a large “L”, with the town center resting comfortably in the crook of the two main intersecting roads. It housed around four hundred families, and Esra had always appreciated that there were enough people to know practically everyone but not so little as to know everyone’s business. Her grandparents’ farm was located at the eastern edge of one of the main roads, about a twenty minute stroll from the central intersection. It was a small town, but everyone seemed willing to look out for each other and it was generally a happy place. The townsfolk especially prided themselves on creating witty allusions to their village name. “I Sorley need a drink” and “a Sorley boring place” were such common phrases that the people who wandered through the town en route were bound to give a startled look when first approached with such a turn of tongue. In fact, the alehouse held a contest at every spring Trader’s Day to see who could come up with the most amusing new idiom. Cane and Esra spent the weeks before the challenge coming up with all sorts of ludicrous sentences.

Like all other towns and cities, Sorley was part of the Kingdom of LeVara, and King Keridon had been the ruler for almost a decade. Although his father before him was fairly popular as a strong and intimidating sovereign, his son Keridon was somewhat weaker willed. Even though the current King was of middle age, he seemed to be more interested in frivolous gaieties such as hunting parties and his Queen’s sitting ladies than making progress with the common people. But his taxes weren’t abhorrently high, and although he appeared somewhat disinterested and dimwitted, he was not an unkind ruler. His distaste for all things gloomy and resentful assured that he never treated his people too harshly.

The King and Queen had two children, the eldest a son named Bronnen who was about Esra’s age, and a younger boy named Samuin. The assurance of an heir with an extra male was reassuring, and luckily Bronnen seemed to take after his grandfather, not his father. The only concern the people of Keridon’s Kingdom had was that if anyone were to invade, the army would never be trained or ready in time to even think of defending the realm. But then again, that had not happened for hundreds of years, and there was no reason why it would now.

The Kingdom where Humans resided was split in half by the impressive Naduri River, a massive torrent of Water that ran from beyond the northern border of LeVara until splitting into a fork just before the southern edge. Nestled in between the fork of the river was The King’s Hold, where the royal family and other nobles lived. The only place to cross The Naduri River’s massive berth was by Grey Thorn Pass, located in the relative center of LeVara. Bordering the entire northern expanse were the Eshomee Ledges, the vast mountain range which housed the Elves. Their capital, The Veiled City, was on Idona, the largest and most imposing mountain in the range. The Elves seemed to be secretive people, as Esra had never met one nor knew anyone who had met one besides Cane. And he never said much about it.

Running down the western border of the Kingdom were The Frost Grounds, a barren, cold place that stretched downwards until it collided with The Stone Sea. No one knew how far The Stone Sea continued, for any who had

tried to find the end of the horizon had never returned from their voyage. To the southeast was the dense Fira Nadim Forest, which the Unni inhabited. The Jade Gardens bordered the eastern end of LeVara, creeping north from the forest until Fire Lake, the residence of the Shendari. Esra knew very little of the Unni or Shendari people, but was hoping that the topic would be addressed at some point in her learning.

Although Humans were curious creatures at heart, most people knew little of the communities of non-Humans and had never been more than a town or city away. There was not much need for travel, as the town provided for the most basic needs, and Trader’s Days allowed for more variety in goods and peoples. Nearly all the inhabitants of Sorley were farmers, and the fields required a most constant attentiveness that did not bode well for unneeded travels. Aside from the traders who visited twice a year, Cane seemed to be the only one in town with extensive knowledge of the world outside and its many different races.

The fact that Cane was an educated man, when most barely knew how to read or write, helped allay the fears of his scandalous pursuit of knowledge into something like avid curiosity. While some people took pity on the lonely status of Cane, others had a faint aversion to him, and superstitious fear ensured that they kept such thoughts to themselves. While most agreed that he was quite eccentric, surely the possession of such knowledge would eventually cause such a thing to occur. His eccentricities were harmless, they decided, and if nothing else he was a quirky, slightly removed old man.

Esra

Esra